Monsters

Monsters

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia: cum paralipomenis historiæ omnium animalium. Bartholomæus Ambrosinus … labore, et studio volumen composuit; Marcus Antonius Bernia in lucem edidit (Bologna, 1642), title page with portrait of Ferdinando II, Grand-Duke of Tuscany; 1610-1670.

The inclusion of the portrait of Ferdinando II de’ Medici (1610–70), Grand Duke of Tuscany, on the title page of one of Aldrovandi’s most famous works, his Monstrorum historia: cum paralipomenis historiæ omnium animalium. Bartholomæus Ambrosinus … labore, et studio volumen composuit; Marcus Antonius Bernia in lucem edidit (Bologna, 1642), was an acknowledgment by his editor, Marcus Antonius Bernia (fl. 1638–61), of the support of the grand duke for the publication. The patronage of the De’ Medici grand dukes had been vitally important for Aldrovandi also, although his principal connection had been with Ferdinando II’s granduncle, Francesco I (1541–87).

Aldrovandi had visited Francesco I at Florence in 1577, in an attempt to secure patronage. His visit was a resounding success on three counts: he developed a good working relationship with Francesco I which lasted until the grand duke’s death ten years later; this, in turn, meant that he benefited from access to Francesco I’s own collections; and, lastly, he met Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627), Francesco I’s gifted court painter, who would later produce wonderful images for Aldrovandi also. Indeed, Jacopo’s brother Francesco, and his cousin, Francesco di Mercurio Ligozzi, also found employment at Bologna with Aldrovandi. Jacopo would later immortalize two coiling vipers, sent by Francesco I to Aldrovandi as a sign of his favour towards his enterprise.

The support of the De Medicis was vital to Aldrovandi, particularly as he had alienated his cousin, Pope Gregory XIII (1502–85), by his rather injudicious use of his ‘Dragon of Bologna’ in his museum. Aldrovandi summarized the importance of his relationship with Francesco I as follows:

Beside the other favors that His Highness did for Doctor Aldrovandi, he gave him many rare and beautiful things, promising him in the future that he would give him part of anything that befell him from foreign hands, and every time that he had two he would give him one, as he has done since, having sent plants, seeds, metals, birds depicted live and other things. One can see this in the Museum of Doctor Aldrovandi and likewise in his histories, where he remembers the Grand Duke, as he does for all the others who have liberally enriched his Theater of Nature.[1]

As Findlen notes, if Aldrovandi in his own mind was the new Aristotle, then undoubtedly Francesco I was his Alexander.[2] Francesco I’s death in 1587 and the elevation of his brother Ferdinando I (1548–1609) was a blow to Aldrovandi for though Ferdinando I continued to offer patronage to Aldrovandi, the Bolognese natural historian no longer had the favoured status he had enjoyed during the reign of his brother.

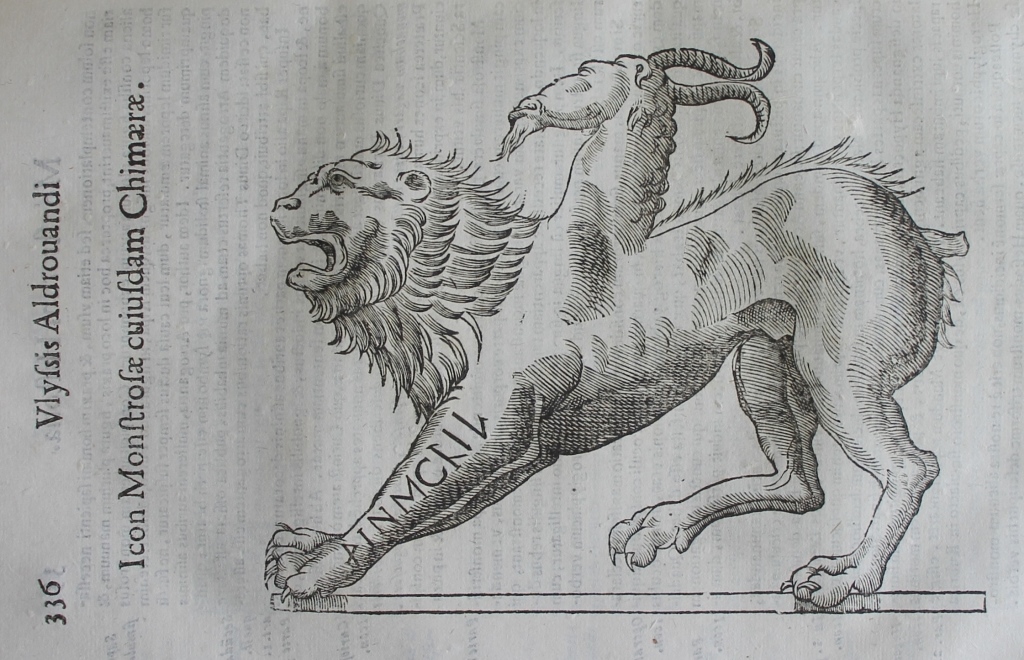

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia: cum paralipomenis historiæ omnium animalium. Bartholomæus Ambrosinus … labore, et studio volumen composuit; Marcus Antonius Bernia in lucem edidit (Bologna, 1642), p. 336, chimaera image.

One of the many joint interests of Aldrovandi and Francesco I had been in monsters – especially dragons.[3] Aldrovandi had included mythical monsters in other volumes – his ‘Sarmatian sea snail’ lurked in his book on Mollusca, while his Serpentum, et draconum historiæ libri duo Bartholomæus Ambrosinus … opus concinnauit (Bologna, 1640) had included rather more terrifying mythical monsters, such as his Dragon of Bologna, Basilisk of Warsaw and Winged Dragons, not to mention strange creatures of the deep such as the Sea Monk and Sea Bishop. In the volume specifically devoted to ‘monsters’ he drew together a host of disparate material, including what he considered to be human ‘monsters’ alongside ancient mythical monsters such as the chimaera, an image he had used in other volumes.

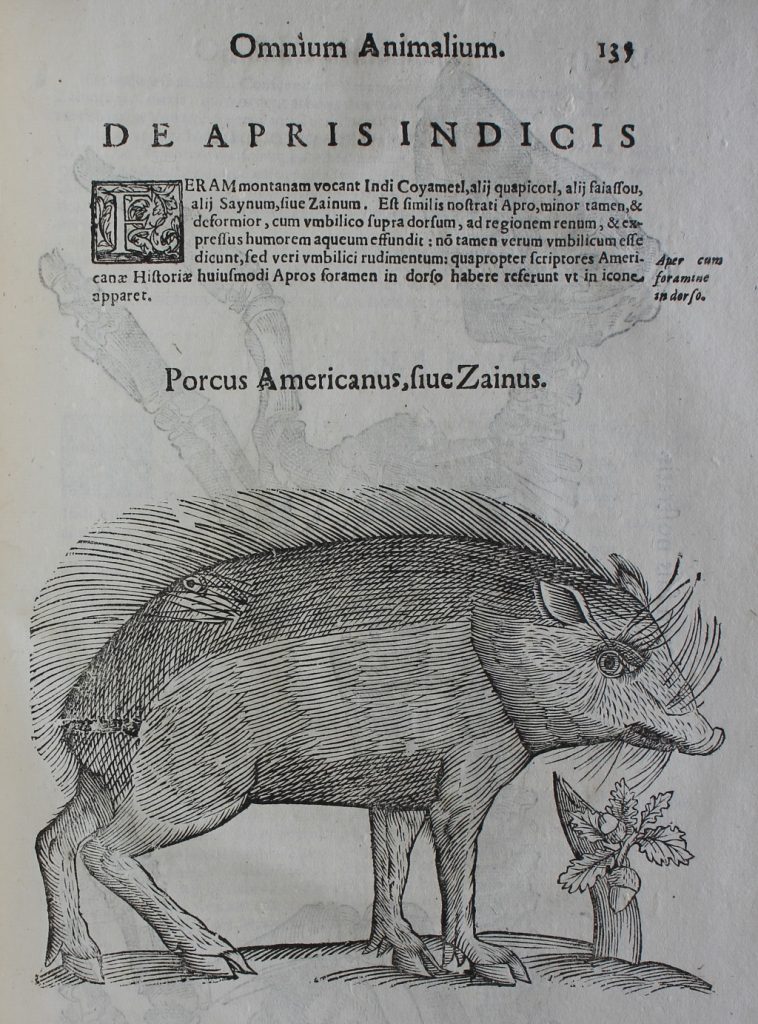

Paralipomena accuratissima historiae omniae animalium, quae in voluminibus Aldrouandi desiderantur in Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia: cum paralipomenis historiæ omnium animalium. Bartholomæus Ambrosinus … labore, et studio volumen composuit; Marcus Antonius Bernia in lucem edidit (Bologna, 1642), p. 135, collared peccary (Porcus Americanus).

Just as Aldrovandi had included monsters in his other volumes, so too did he include what we would consider to be ordinary animals in his monsters volume. One such was his image of a collared peccary, which was based on watercolour by Ligozzi. The collared peccary’s Latin name, ‘Porcus Americanus’ drew attention to its natural habitat, for it, like Aldrovandi’s giant anaconda in his volume on reptiles, were discoveries in the New World. As Groom notes, the profile view adopted in this illustration of the collared peccary was replicated throughout Aldrovandi’s volumes and may have been an editorial choice, making the images more uniform.[4] Ligozzi visited Bologna in 1577 (possibly to oversee the reproduction, by engravers, of this and other images).[5]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library.

Sources

Findlen, Paula, Possessing nature. Museums, collecting, and scientific culture in early modern Italy (Berkeley, 1996).

Groom, Angelica, ‘Early Modern Natural Science as an Agent for Change in Naturalist Painting: Jacopo Ligozzi’s Zoological Illustrations as a Case Study’, in Beck, David (ed.), Knowing Nature in Early Modern Europe, (Abingdon, 2015), pp 139-164.

[1] Findlen, Paula, Possessing nature. Museums, collecting, and scientific culture in early modern Italy (Berkeley, 1996), p. 358.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., p. 20.

[4] Groom, Angelica, ‘Early Modern Natural Science as an Agent for Change in Naturalist Painting: Jacopo Ligozzi’s Zoological Illustrations as a Case Study’, in Beck, David (ed.), Knowing Nature in Early Modern Europe, (Abingdon, 2015), p. 150.

[5] Ibid., p. 152.